15 Jun 2015

Since the beginning of the Syrian Revolution in 2011, the stories of female Syrian refugees in Lebanon, Often separated from their husbands and family, have been told through various media and reports, expressing great concern for their safety. As these women struggle to survive, many have experienced trauma and sexual targeting by Syrian and Lebanese men inside and outside the camps where they live. Some art initiatives are trying to create an image of these women beyond that of a victim, giving them voice through works that sensitively look at their lives and situations.

Some artists have addressed “How does one discuss Syrian women who have sought shelter in Lebanon without falling into the trap of sensationalism?” by allowing the women to express themselves. Such is the case of Aglaia Haritz, from Switzerland, and Abdelaziz Zerrou, from Morocco, both visual artists.

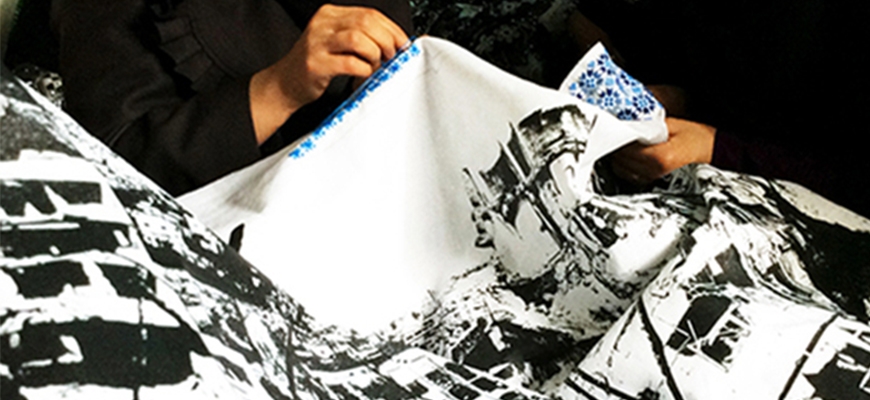

Haritz ad Zerrou met in Paris in 2011 and decided to work together on a project, Embroiderers of Actuality. For this undertaking, they ask women in different locations — Cairo, Casablanca and Marrakech and this year Beirut — to create embroidery. Afterward, the two artists draw images, including on the embroidery, and create sculptures influenced by the discussions they have with the women. The works are then displayed in yet a different country.

“Embroidery is an excuse to get in touch with women from conservative societies and to get to know their world and stories,” Haritz said. “We want to show these aspects in art spaces to bring light to their situation. While the women embroider, we talk to them, and we make sound recordings and videos, a kind of sound sculpture that reflects the work atmosphere.”

Each city presents different situations and stories, so each piece is different from all the others. “For example, in Beirut, we met with the women in the Basmeh wa Zeitooneh organization in Shatila camp. We sensed a strong issue of identity, so we took pictures of them and combined them with the embroideries, so we could highlight the women’s personalities,” said Haritz. “It was much easier to access and talk to them than in Morocco and Egypt.”

Embroidery allows the artists to spend enough time with the women to bring out meaningful stories about their lives. As Haritz explained, “Then we mix their masterpieces with contemporary art, from tradition to modernity, in order to confront them and give a complete picture of the situation.”

Photography is another medium being used to approach Syrian women in Lebanon. The Syrian filmmaker and photographer Omar Imam arrived in Lebanon from Damascus as a refugee at the end of 2012. He began working with refugees through the Danish Refugee Council, which asked him to visit and photograph daily life in five refugee camps. The exhibition of his work was held in December 2014, focusing on a teenage audience to inform them of refugees’ situation without engaging in stereotypes. This experience, which Imam called “too fast and not personalized enough,” led him to take part in another project, Live Love Refugee, financed through a grant from the Arab Fund for Art and Culture and its Arab Documentary Photography Program.

Imam is currently editing a video set to music that consists of photographs of Syrian families and quotes from them, focusing mainly on women, after noting that the majority of the camps’ inhabitants are women. “I realized in talking to them that their lives are very hard in Lebanon,” Imam said

Imam said, “They are, especially in the camps, where precariousness and loneliness are prevalent factors, subjected to much more sexual violence and early marriage than before the war in Syria. When I heard these stories, I chose to document them, but not in the media’s way. I didn’t want to produce another documentary simply showing the usual pictures of them in their current living situation. I play on each person’s story to create a dreamy atmosphere. It is very conceptual. I focus on the important parts of the stories they tell me to reproduce them physically, with symbolic details. For example, I pictured a woman whose husband had left her during the war with her children, posing as they would for a normal family picture, but next to a man of straw. I want to attract the world’s attention to their situation, not by taking just another picture of a refugee, but also adding some dreams and symbols. [The refugees] are sick of the media and photographers approaching them. I had to build a very solid bridge for them to trust me.”

One of the pictures that really touched Imam was one of a 16-year-old girl wearing a bridal dress and dragon’s wings. She appears to throw a fireball and looks very angry, yelling. The accompanying quote reads, “I wish to become a dragon and burn the scarves and everything in that tent.”

“This girl’s story is not that unusual,” Imam said. “She was married by her family and refused to have sex with her husband on their wedding night. He called his family for help, so they came to restrain her and beat her. Then she claimed not to be a virgin, so her own family beat her as well. To survive, she told her family and her husband’s that she was actually a virgin and spent a night with her spouse. The next day, she asked for a divorce. I had to find a creative way to express her anger, but also her strength, through details that are not realistic but reflect her feelings. Initially, Imam did not want to use her story. “It was too hard for me [to handle],” he admitted. “But if it is too hard for an artist to talk about this issue, who will?”

Imam focused his project on women, because he felt that they had more moving stories and played large roles in the camps. “Art is the best way for me to talk about [women’s] situations, because women in our society don’t have a direct relationship to the media. Men and even female family members prevent them from talking and [answer] on their behalf. You can’t hear their voice, so it’s our mission, as activists and artists, to make this possible. But I never reveal tears, because they are the survivors. I want them to express it in my pictures.”

Not victimizing the women is also an important rule in the work of Embroiderers of Actuality. Haritz said, “From a European perspective, Arab women are submissive and exploited. It is important to confront this stereotype with the reality. Since it’s hard in conservative areas to access them, art is a bridge for them to be heard and to show their real condition, whether they are fragile, conservative, brave or liberal. What I admired the most in Beirut is that the Syrian women we met were really supportive of each other and able to share everything. They showed strength, and I’m happy to have been able to testify to that.”

عربي

عربي