11 Mar 2015

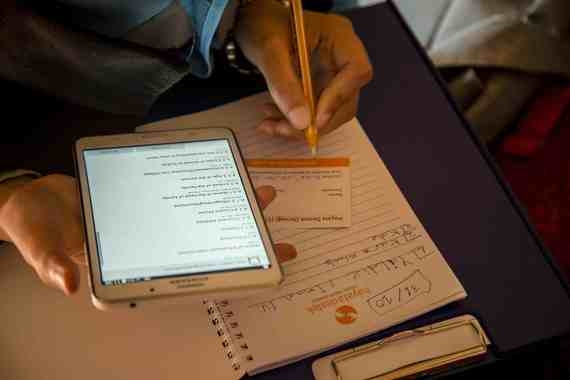

In the “Situation Room” there are cards stuck on the wall. Some of the 607-mile long Turkey-Syria border. And some of an unnamed town, in the streets to the south a line is drawn in with thick red marker. Below, the words “Sniper Zone”: the place is literally within firing range of the warzone. These cards are in the Istanbul office of humanitarian organization Support to Life. Sema Genel Karaosmanoğlu, a founding member, has asked me not to photograph them. Sema has every reason to be cautious. Four weeks ago one of her employees, 26-year old Kayla Mueller from Arizona, was killed in Syria, a year and a half after being taken hostage by ISIS. For their part, ISIS claim that Mueller was killed in Jordanian air-strikes on their self-declared capital of Rakka. But who can say whether this is true? Syria’s civil war has lasted now almost four years. Well over 200,000 deaths have been counted and mourned. How can anybody, sitting at a comfortable desk, hope to describe and do justice to such a colossal tragedy? Of a population formerly numbering 23 million, seven million are currently refugees within the country itself, while a further three million have fled to other countries. That’s almost half of the entire population. In the U.S. that would equate to 150 million people. Unimaginable. The U.N. is describing the Syrian refugee crisis as the worst since the Rwandan genocide. Support to Life has been supporting Syrian refugees in Turkey for two years now. 4,300 families, over 20,000 people. These are above all so-called “urban refugees”, that is, people who don’t live in refugee camps but rather in villages and towns, inhabiting for instance in former cattle-sheds or abandoned buildings. The refugee camps themselves are mostly run by the Red Cross, or its Islamic counterpart the Red Crescent. At every stage of the process, Support to Life uses digital technology: from communication with refugees, to concrete delivery of aid, to measuring their impact. The field workers on the ground are equipped with tablets, and they carry them from house to house, identifying those in need of help. To do this they fill out a “baseline survey” on their tablets, which immediately evaluates using a points system whether the family will get support. A second questionnaire, distributed later, can evaluate in a straightforward way how effective the aid efforts were. So that the refugees can buy food and hygiene products, they receive cash-cards, which are topped up every month with credit, so that they can go shopping themselves in selected nearby stores. Previously, every family used to receive a standardized aid package. “The cash card system gives them back a bit of dignity,” says Sema. So why not just give them cash? Two reasons: Firstly, Support to Life wants to ensure the funds are only used to buy certain goods. And secondly, the system allows the organization to analyze what people actually need, and in what quantities. “Up until now we’ve collected a lot of data, but we do little to use it,” says Sema. This raises a data-dilemma that Zara Rahman at Re:Publica and Ben Mason in The Guardian have already explored: namely which data, and how much, should you collect with the intention of helping people?

عربي

عربي