10 Nov 2015

A seemingly endless mass of people continue to flee Syria for a new life — any kind of life.

The Turkish government has warned that up to a million people may begin to cross from Syria into Turkey, Lebanon, and Jordan this winter, and another two million could be displaced within their own country.

The United Nations estimates that 13.5 million people in Syria are in need of humanitarian assistance, 6.5 million have been displaced inside the country, and a staggering 4.2 million have fled in fear for their lives.

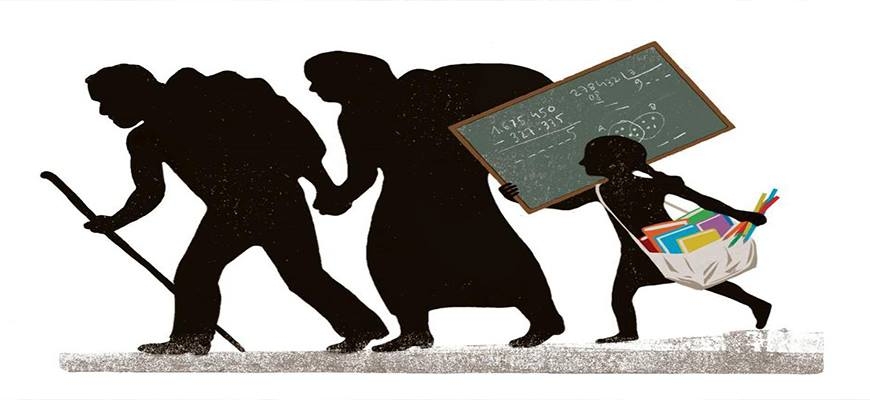

But this is a war where not only are the victims mainly civilians, but where children constitute half of all the displaced and exiled.

Already there are two million Syrian child refugees — the biggest single cohort of exiled children since 1945. If the Turkish government estimates are right, the numbers will rise by another 25 percent by next spring.

And while a country such as my own, the United Kingdom, stalls on taking fewer than 4,000 Syrian child refugees a year, child refugees are on the streets, in camps, or in shacks or tents in the three countries bordering Syria.

This is the ugly heartland of a lost generation.

Since the crisis began, child marriage rates have doubled, according to the charity Girls Not Brides, from 12 percent to 26 percent. Tens of thousands of boys and girls are being used as child laborers, and thousands more have been trafficked by gang-masters.

And from a school-age population, almost all of which were in school in pre-war Syria, now there are more than one million children out of education, with little prospect of returning.

The repeated voyages, on what have become known as “coffin ships,’’ across the Mediterranean are only one sign of how much hope has given way to despair.

Tragically, Syrian parents seem to have lost confidence in any future for their children in the region. Who in their right mind would put their children into a boat unless they think it’s safer to be at sea than on land?

But who in their right mind wouldn’t want their children to be in the safe haven of a school and planning for a future? If education were available to their children in Lebanon, Jordan, and Turkey, desperate parents could see a glimmer of hope and a future.

Two years ago I called an emergency parliamentary debate in the United Kingdom, outlining a plan to educate Syrian refugees in those countries. Children were falling through the safety net, locked out of humanitarian aid that focused on food and shelter, and last in the queue for development aid, which was primarily directed to long-term objectives and not to crises.

Since then, with the backing of Lebanese Education Minister Elias Bou Saab, more than 170,000 Syrian refugees have been enrolled for school under a unique double-shift system, with the number increasing.

It costs $500 per child per year, or $10 per week. The Syrian children receive their schooling as part of a late-afternoon shift in existing Lebanese schools once the local children have gone home, or join Lebanese students in the first shift earlier in the day. This is a simple and effective use of scarce resources.

There is no shortage of classrooms or any lack of teachers to prevent the expansion of this double-shift system across the three countries. But the breakthrough that would offer schooling and a safe haven to the lost children has yet to come.

So what is stopping us doing more? Sadly, it is money. Only 2 percent of global humanitarian aid goes to education. A program needs to be established to coordinate and fund education in emergencies. The program would guarantee that even if children are out of their homes, their neighborhood, or their country during conflict or disaster, they will not be out of a school.

The first test of our resolve is to find the money to help the Syrian refugee children in Lebanon, Turkey, and Jordan. If we are to deliver on our guarantee of education without borders, the plan has to cater to the needs of 510,000 refugee children in Lebanon, at least 215,000 in Jordan, and upwards of 400,000 in Turkey. And in the next few weeks the international community — old donors and potential new ones — will be asked to increase the $100 million that we have already raised for Lebanon with another $400 million.

If we can educate child refugees in some of the most troubled countries in the Middle East, then our next step must be to help child refugees in Africa. Help is needed, from war-torn South Sudan to the conflict-riven Democratic Republic of the Congo — and in Asia, where the plight of refugees fleeing Myanmar and the destroyed schools of Nepal demands global action. Neither must we forget the needs of millions of children displaced and uneducated on the Afghan-Pakistan border. The world cannot afford to lose a generation of precious children to life in refugee camps, which more and more risk becoming permanent settlements of human misery.

If we fail to act, these children will remain prey to child labor, child trafficking, and early marriage, and susceptible to the influence of terrorists. But if children have schooling, the evidence is that families will stay in the region. Of course food, security, and health care are essential for survival. But education offers something more: It can give young people hope — the promise they can plan for a future, the prospect of preparing for a job and a career in more peaceful times, and the ability to dream of a future.

عربي

عربي