29 Jul 2015

As the crisis in Syria continues apace, more than 9 million people are now estimated to have been displaced since the outbreak of hostilities in March 2011.

In addition to humanitarian and crisis response activities on the ground, the crisis has spawned a wealth of research work, which aims to guide the international community’s response and next steps.

One recent study by Tejendra Pherali of the University College London’s Institute of Education and Karl Blanchet of the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine on the plight of Syrian refugees shows the potential of putting international development research results into practice to concretely help people on the ground.

While an estimated 6 million displaced people remain within Syria’s borders, the Office of the U.N. High Commissioner for Refugees estimates that more than 3 million have fled to neighboring Turkey, Iraq, Lebanon and Jordan. Jordan and Lebanon are two small countries that have accepted a large proportion of these refugees, hosting 600,000 and 1.2 million, respectively.

Pherali and Blanchet studied the government response to the refugees’ health and educational needs in Jordan and Lebanon, and are hopeful that their findings will persuade the authorities to adopt a new approach.

Needs assessments reports in refugee contexts show that after safety and shelter, access to health and education is a priority for newly arrived refugees. It is important to establish a rapid medical response to prevent disease breaking out or spreading, and as there are always a high proportion of children, it is important for them to continue their education.

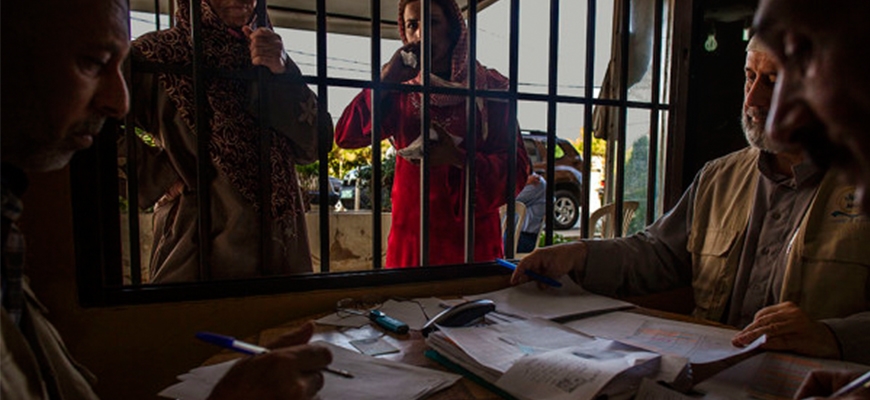

In Lebanon health is privatized, so UNHCR is subsidizing health coverage to the tune of 75 percent of the total costs for treatment, medication and consultation. In Jordan, there is a state scheme to cover primary and secondary health needs and, while the country is struggling to provide health coverage, rules concerning qualifications and work permits for refugees prevent qualified Syrian refugee doctors from being employed.

In terms of education, 52.1 percent of Syrian refugees are under 18 and 34 percent are of school age.

In Lebanon, eligibility for state schooling is based on being resident in the country for two years, so newcomers are disqualified — and when they eventually qualify, have missed two years of their education. As only 29 percent of local children go to state schools, these schools have a disproportionate number of refugee children, creating local tensions. In Jordan, meanwhile, researchers found a different set of problems when they visited the Za’atari refugee camp: Only teachers with a Jordanian qualification are allowed to teach.

Given the low status of teaching in a refugee camp, teachers are usually newly qualified and inexperienced, so teacher-pupil relations are poor, with resultant discipline problems and consequent low educational standards.

Pherali outlined the moves the research team is making to broadcast the findings and explained how they will be used to spur changes to relieve tensions for the governments and refugees involved.

First, researchers learned that refugees’ health and education needs are interlinked and mutually dependent — a departure from the traditional approach where education takes second place to health.

“Getting children back to school is important because it restores a sense of normality, and helps save lives, as teachers identify children’s health and other problems,” Pherali explained, adding that a more holistic approach is needed in refugee or other humanitarian crises, with greater collaboration between government ministries. Secondly, researchers found that in Jordan there was a huge informal sector including trained professionals among the refugee population, which could help supply their health and education needs. In both countries a change in regulations — in Lebanon on school eligibility and in Jordan on the use of qualified refugees — could help refugees and relieve some of the strains for state provision.

The research team’s findings call for health and education to be integrated, with government regulations modified in crisis situations.

With the aim of encouraging government and nongovernment actors to rethink how to plan and implement intersectoral programs and service “packages,” Pherali explained the team’s recommendations will be disseminated to the Lebanese and Jordanian health and education ministries, as well as humanitarian agencies that provide health and educational services to Syrian refugees.

The next step, Pherali explained, is to open up the debate to as broad a group as possible and not expect it to have immediate effect, since the impact of research does not happen in a linear way.

“What we can do is to continuously encourage the debate and engage with practitioners and government ministers so they start thinking in a different way about intersectoral work and policies,” he said.

With the number of people forced to flee their homes around the world having exceeded 50 million for the first time since World War II — stretching host countries and aid organizations to breaking point, according to figures released by UNHCR in June — these findings could help set a sea change about how to best cater to their needs.

عربي

عربي